Beneath the surface of an ever-snappy Linux machine, a bustling city of invisible workers known as “processes” are tirelessly running the show. From printing documents to streaming music, each task is a dedicated citizen in this microscopic metropolis, governed by the intricate laws of the Linux kernel.

In this article, we’ll shed light on this hidden world, delving into the fascinating anatomy of a process, the intricate rules of their coexistence, and the tools you can wield to become the mayor of your digital town.

Introduction

A process is a running instance of a program, amidst its execution. It is more than just a piece of text (namely, the text section or the code section), though. When we talk about a process, we also need to take into consideration the resources allotted to it, such as Open files, Pending signals, Internal Kernel data, the State of the processor, Memory address space, the Threads working in unison under it, and also the Data section. These details, of every process, need to be efficiently managed by the kernel to perform effectively.

Note: “Threads”, as “objects of activity under a process”, is exceptionally explained by Robert Love in his book “Linux Kernel Development”. The kernel, in reality, only knows and deals with threads. A process happens to be a set of threads sharing resources, and having the same Group ID (basically the Process ID).

Each thread in the Linux kernel also has its own set of resources, such as a Unique Program Counter, a Process Stack, a set of Process Registers, and a heap it shares with other threads under the same Group ID.

There are two types of Virtualisations provided by the Linux kernel to every process: Virtualised Processor and Virtualised Memory. The “Sharingan” of the kernel puts the process into a “Genjutsu”, tricking it into believing that it is the only existing process in the kernel, and occupies all the available CPU time and memory resources alone. (reference: “Naruto”, a Japanese anime). As we’ve seen above, a thread shares the memory abstraction with other threads under the same process, but each has its own virtualised processor.

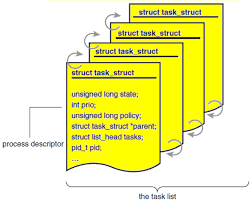

The Process Descriptor

All the processes spun up by the Linux kernel are stored in a Doubly-Circular Linked List, namely the task list. In the header file linux/sched.h is defined a structure, task_struct which is essentially the process descriptor. As the name suggests, it contains all the information that is possibly out there about the process.

Previously (before Linux Kernel v2.6), the task_struct structure was directly stored at the end of the kernel stack (upper or lower end, based on the processor’s architecture) of every process. However, after the release of v2.6, the kernel now allocates memory to the task_struct structure based on the slab allocation algorithm (a slab is a set of physically contiguous pages of memory, and a cache is a set of slabs), improving the struct’s access times. Now, since the memory for process descriptors is dynamically allocated, a new structure was introduced into the kernel, struct thread_info. This structure is now stored at the end of the kernel stack, and contains a pointer to the task_struct process descriptor.

Every process in the kernel is uniquely identified with its Process ID (the PID). The kernel has an opaque/abstract data type pid_t, which basically stores the pid values as integers. The kernel, by default, defines the maximum number of processes that can be spun up by the kernel without replacing other processes in the circular task list. System administrators can easily tweak this by changing the value defined in the /proc/sys/kernel/max_pid file; care needs to be taken as this change may bring in compatibility with older applications running on the system.

The kernel also has a macro named current, which allows quick and easy access to the process descriptor of the currently running task (it is processor arch dependent, though). This may not be a feasible option in architectures where there are very few registers to deal with; hence, they can use the thread_info structure to access the process descriptor, in which they simply need to calculate the appropriate offsets to locate the structure inside the kernel stack.

States of a Process

The above flow diagram perfectly describes the lifecycle of a Linux process.

TASK_RUNNING- The process is either currently running, or waiting to be scheduled in the runqueue. If a process is in the user space, this is the only possible state in which the process can be.TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE- The process is either blocked by a condition to be fulfilled, or is currently sleeping. The process in this state can also be woken up by sending appropriate signals.TASK_UNINTERRUPTIBLE- The process is in a state similar to that ofTASK_INTERRUPTIBLE, the only difference being it cannot be woken up even by sending signals. This is also the reason why it is less frequently used compared toTASK_INTERRUPTIBLE.TASK_TRACED- The process and all its resources are being traced by another process. Generally the tracers are debuggers, which help log the tracee’s activities. A good example is theptrace()syscall, which allows the tracer to gain complete control over the execution of the tracee.Note: The tracee is temporarily reparented to the tracer in the

ptrace()syscall.TASK_STOPPED- The process has been terminated, and is not allowed to run any further.

The function set_task_state(task, state) is called to change the state of the process.

The Process Tree

The init process, having a Process ID of 1, is the mother of all processes, as all other processes spun up are eventually children of the init process. The init process is spun up in the last stage of the boot-up process. All the initscripts are executed, and the required child processes are spun up.

Note: The kernel maintains separate lists for processes that are *ptraced**, saving a lot of time when all the siblings that are being ptraced need to be reparented to their original parent.*

Creation of a Process

In the Linux kernel, there are two major function calls to execute the creation of a new process in the process family tree: fork() and exec().

The fork() function creates an exact copy of the parent function as a child, which only varies in PID, PPID (Parent PID), and some pending signals, usually not inherited. All other properties of the parent are copied into the child. The exec() function then loads a new executable binary into the address space allotted to the child, and starts execution.

Copy-on-Write

At this point, you may be wondering if copying the parent’s resources into the child’s address space may cause a high overload. Indeed, this is the case. It is even worse when the process executes a completely different program, and the copy goes into the garbage! In comes Copy-on-Write to the rescue.

Copy-on-Write(COW) is a technique smartly implemented to mitigate this overload as much as possible. Initially, when the child is forked from the parent, the resources aren’t copied; they share a single copy. However, if the parent or child attempts to write to this single shared copy of data, separate copies are created and allotted to the parent and child processes, respectively. No action is taken if either reads from the shared copy, as a read does not affect the stored data.

However, COW duplicates the page tables and process descriptors, which is the only overhead incurred. The vfork() syscall addresses this issue by giving the child read-only access to the parent’s page table entries. The parent is blocked from writing into the page table until the child either terminates or calls exec(), and the child also cannot write into the table.

Following is the flow of execution of code when the fork() syscall is triggered:

clone()syscall (called byfork()) - accepts flags that indicate which resources need to be shared between the parent and the child.do_fork()syscall (called byclone()), defined inkernel/fork.c.copy_process()syscall (called bydo_fork()) :dup_task_struct()- creates a new kernel stack,thread_infoandtask_structstructures for the child, identical to those of the parent.- Resource limit checks are performed to see if the newly spun-up process will exceed maximum process limits.

- Required members of task_struct are updated to give a unique identity to the child process.

- The state of the child process is set to

TASK_UNINTERRUPTIBLEto ensure that the task cannot run yet. copy_flags()- updates the flags of the child’s process descriptor.alloc_pid()- allocates a new PID to the child process.- The resources are either copied over or shared, depending upon the flags passed into the

clone()syscall. - Cleanup code is executed, and a new pointer to the process descriptor of the child is returned.

If the above code executes perfectly, then the child process is put into the runqueue, ensuring that it runs before the parent to eliminate any overhead caused by COW.

Kernel Threads

It is not just the user space applications that must execute code, but also kernel functions. The Linux kernel takes care of this using kernel threads; the only difference between the two is kernel threads don’t have memory spaces allotted. The kernel threads are also schedulable and preemptible, making the Linux kernel a fully preemptible kernel, drastically increasing its performance.

The Linux command $ps -ef lists all the kernel threads spun up by the kernel. The kernel threads, unlike other threads, are not children of init. They are the children of kthreadd, having PID 0, and consequently, a new kernel thread can only be spun up from another kernel thread only.

Termination of a Process

The code for the termination of a process is under the do_exit() function, defined in kernel/exit.c. The flow of execution of code when the do_exit() syscall is triggered is as follows:

The

PF_EXITINGflag is set to indicate that the process is terminating.del_timer_sync()- removes associated kernel timers.exit_mm()- release the address space mapped to the process; if it is the only process under the respective Group ID, the address space is destroyed.exit_sem()- all semaphores held by the process are removed.exit_files()andexit_fs()- decrements the usage count of the mapped files and the respective filesystems; if the usage count reaches zero, the corresponding objects are destroyed.Update the task’s

exit_code, which is to the parent when theexit_notify()function is called. The parent can retrieve theexit_codeinformation and perform necessary actions, or ignore it. The child’s state remainsTASK_ZOMBIEuntil the parent is notified about the termination of the child.schedule()- The core scheduler code is invoked to trigger the scheduler and schedule the next process for execution.All the remaining resources are returned to the kernel, and will be available for allotment to new processes.

The process descriptor is destroyed only after the parent notifies the kernel that it is uninterested in retrieving information about its “zombie” child.

release_task()is invoked, which performs the following tasks:__exit_signal()->__unhash_process()->detach_pid()– deallocates the PID of the terminated process.- Cleanup code is executed, and kernel stats are updated.

- The slabs and cache allotted to the

task_structprocess descriptor are released.

Handling of Parentless Processes

There may be cases where the parent process gets terminated before its child. In such cases, a fallback mechanism must be in place so that the kernel can reparent the child to a new process or directly to the init process. If this isn’t done, the child processes, which will terminate in the future, will forever be in the TASK_ZOMBIE state, wasting system memory resources.

In the Linux kernel, this is implemented within the find_new_reaper() function called by the forget_original_parent() function. Following is the code:

/*

* When we die, we re-parent all our children, and try to:

* 1. give them to another thread in our thread group, if such a member exists

* 2. give it to the first ancestor process which prctl'd itself as a

* child_subreaper for its children (like a service manager)

* 3. give it to the init process (PID 1) in our pid namespace

*/

static struct task_struct *find_new_reaper(struct task_struct *father,

struct task_struct *child_reaper)

{

struct task_struct *thread, *reaper;

thread = find_alive_thread(father);

if (thread)

return thread;

if (father->signal->has_child_subreaper) {

unsigned int ns_level = task_pid(father)->level;

/*

* Find the first ->is_child_subreaper ancestor in our pid_ns.

* We can't check reaper != child_reaper to ensure we do not

* cross the namespaces, the exiting parent could be injected

* by setns() + fork().

* We check pid->level, this is slightly more efficient than

* task_active_pid_ns(reaper) != task_active_pid_ns(father).

*/

for (reaper = father->real_parent;

task_pid(reaper)->level == ns_level;

reaper = reaper->real_parent) {

if (reaper == &init_task)

break;

if (!reaper->signal->is_child_subreaper)

continue;

thread = find_alive_thread(reaper);

if (thread)

return thread;

}

}

return child_reaper;

}

After obtaining a new reaper via the above function, all the siblings are reparented, which is implemented in the code below:

/*

* This does two things:

*

* A. Make init inherit all the child processes

* B. Check to see if any process groups have become orphaned

* as a result of our exiting, and if they have any stopped

* jobs, send them a SIGHUP and then a SIGCONT. (POSIX 3.2.2.2)

*/

static void forget_original_parent(struct task_struct *father,

struct list_head *dead)

{

struct task_struct *p, *t, *reaper;

if (unlikely(!list_empty(&father->ptraced)))

exit_ptrace(father, dead);

/* Can drop and reacquire tasklist_lock */

reaper = find_child_reaper(father, dead);

if (list_empty(&father->children))

return;

reaper = find_new_reaper(father, reaper);

list_for_each_entry(p, &father->children, sibling) {

for_each_thread(p, t) {

RCU_INIT_POINTER(t->real_parent, reaper);

BUG_ON((!t->ptrace) != (rcu_access_pointer(t->parent) == father));

if (likely(!t->ptrace))

t->parent = t->real_parent;

if (t->pdeath_signal)

group_send_sig_info(t->pdeath_signal,

SEND_SIG_NOINFO, t,

PIDTYPE_TGID);

}

/*

* If this is a threaded reparent there is no need to

* notify anyone anything has happened.

*/

if (!same_thread_group(reaper, father))

reparent_leader(father, p, dead);

}

list_splice_tail_init(&father->children, &reaper->children);

}

There is a separate function, exit_ptrace() to handle reparenting of ptraced processes (after tracing is completed or terminated):

/*

* Detach all tasks we were using ptrace on. Called with tasklist held

* for writing.

*/

void exit_ptrace(struct task_struct *tracer, struct list_head *dead)

{

struct task_struct *p, *n;

list_for_each_entry_safe(p, n, &tracer->ptraced, ptrace_entry) {

if (unlikely(p->ptrace & PT_EXITKILL))

send_sig_info(SIGKILL, SEND_SIG_PRIV, p);

if (__ptrace_detach(tracer, p))

list_add(&p->ptrace_entry, dead);

}

}

Conclusion

We cracked the code on Linux processes! Now we see how programs run, dance with the CPU, and share resources like magic. This isn’t just fancy info; it’s superpowers! We can fix problems, squeeze more juice from our machines, and even build our own stuff. Linux processes are no longer black boxes – we’re in control!